KBC Home

Tour Table

of Contents

Lease

land as it relates to the wildlife refuge

o History

o Pesticide use,

diseases, and flood/fallow program

o Kuchel Act and Questions and Answers (like,

"Is there a smoking gun between pesticide use and

dead waterfowl out there?")

o Lower Klamath National Wildlife

Refuge and Tulelake Refuge including history,

plumbing, waterfowl, operations, effect of power

rate, and endangered species

Karas: Next we we're going to have Mike Green talk a little bit about the lease lands as it relates to the refuge.

History

|

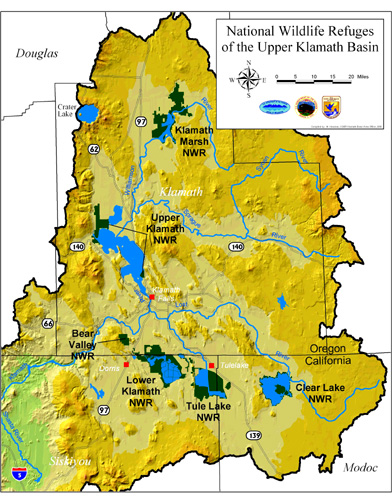

Mike Green: Okay, yes my name is Mike Green. I work for the Bureau of Reclamation. Iím the lease land manager and my job is to run the leasing program which is on two National Wildlife Refuges here in the Klamath Basin. Okay, the lease areas are designated by these gray darker areas. We have about 16,000 acres on Tule Lake, and 5000 acres on Lower Klamath Lake National Wildlife Refuges. These lease areas in Tule Lake were basically carved out of the lake bottoms when the lakes were drained, this began in 1910 when Clear Lake dam was built and Lost River Diversion dam was built in 1912. As the lake waters receded, the Reclamation Service, now the Bureau of Reclamation, began leasing out these lands as they prepared them for homesteading, and that began about 1914, and as these lands were homesteaded and as the lake eventually dried up, it pooled up into a section of the southwest corner of the old lake. |

|

And in

1928, by executive order, this refuge (Tule Lake) was created. Two sumps were

left watered up because of the high concentration of waterfowl and other birds.

The other areas were leased out for farming, and at the time everybody was still

under the understanding that these areas would be eventually homesteaded. Over

here on Lower Klamath Lake, this boundary being the old lake area and before it

was drained, was created in 1908 by executive order which created the Lower

Klamath National Wildlife Refuge. Then in 1912, the railroad built a levy

across this area, between the old lake and Klamath River, which prevented winter

waters from filling up the old lake. The waters in the old lake would drain back

out during summertime, which created a lot of diversity out there. Thus creating

a huge seasonal wetland, along with a few permanent wetlands in the middle. In 1917, Reclamation placed gates in the outlet here (at the railroad levee) in the Klamath Straits, which basically cut off most water entering Lower Klamath Lake. In about the late 1920s, this area was leased out for grazing, and then in the early 30s, growers found they could actually grow grain in certain areas and eventually the Lower Klamath lease lands were created over time. |

Crops

In Lower Klamath, we have grass hay and grain production on this area, down here in this area of Tule Lake we have row crops such as: onions and potatoes, and we also have small grains such as: oats, barley and wheat. We also have alfalfa production. Currently the program encompasses about 21,000 irrigated acres. It is the largest irrigated government farming program in the United States. Our primary goal is to have a low input commercial farming program that benefits the major purpose of the refuge: waterfowl production and other wildlife.

Pesticide use and flood/fallow program

Thereís been a lot of concern about

pesticide use out there. Together with the Fish and Wildlife Service and

Reclamation, weíve created a pesticide use proposal committee which consists of

experts in endangered species, toxicology, environmental contaminants, lease

program management, cultural practices, and this group gets together at various

times of the year and entertains pesticide proposals from the various growers.

We look to see that they donít exceed certain thresholds that are set by

interior policy and that they donít have any long-term/persistent concerns or

leaching concerns. So we really minimized what products are available for use

out there, and also we try not to allow too many products. We do try to really

look at what pests are we trying to target, and what products are the best for

those pests.

With that concern weíve also discovered a way that we might be able to lower pesticide input and also increase compatibility with the major purpose of the refuge, and in 2000 we created a 400 acre strip out in Tule Lake leases, whereby we took cropland out of production and we flooded it for one year, and within that one year we had some water problems in terms of our dikes not holding up causing water fluctuations. What we found out is that we created a vibrant marsh ecosystem within months, its was just incredible the amount of bulrush and other aquatic plants including smart weed that came up. We also noticed right away that we had a large amount of waterfowl and eagles working the area. At the same time we also had some information that indicated that we might be able to reduce soil born pest levels by flooding these areas for a year, which would allow us to lease out "clean" soils if you will, or virgin soils, again, without too many pests in it, in hopes that that might allow the next grower to minimize pesticide inputs.

We did draw samples for nematodes in the soils before we flooded and then we sampled that same area again and we were not able to find any nematodes in our samples after one year of flooding. Talking with Harry Carlson of U.C., he indicated that the same type of results could happen from dry fallow, without the water.

By placing the water on there, weíre creating more habitat and more food, which brings in more wildlife, and certainly makes the program more compatible with the refuge. And weíre working cooperatively with the Tulelake Irrigation District, the growers, the University of California, and Refuge Staff. Weíve recently expanded this program to include areas that are flooded from one to four years, and right now we have a ten year program in place to eventually flood-fallow the entire Sump 3 area, this 10,000 acre unit right here. Whereby weíre doing roughly about 1000 acres at a time, and thatís basically a kind of quick rundown on the leasing program. Iím open for questions

QUESTION: Mike, can you tell us how many people are involved in these lease areas? How many farms does that comprise?

Green: Okay we have roughly about between 50 and 60 individual growers out there.

QUESTION: And whatís the economic impact of those farmers? What do they produce on an annual basis?

Green: Well, if you're looking at the economic impact to the local community, itís been estimated at about 8 million dollars. The U.S. Treasury nets about $750,000 annually.

COMMENT: They generate about 2 million dollars annually revenue to the United States. Different counties also benefit from it. About a half a million, a third to a half million annually...correct? (see above)

What the Kuchel Act has to do with the lease

lands

and Questions and Answers

QUESTION: Can you explain to me what the Kuchel Act has to do with the lease lands?

Green: Okay, there was controversy out here for a lot of years as to whether this area should be homesteaded or left for waterfowl production. And that debate began in the twenties and continued all the way into the early 60s, when Congress debated that issue with Senator Kuchel from California introducing and passing a bill in 1964 that permanently established the major purpose of the Refuge lease lands for waterfowl production, and permanently ended any possibilities of homesteading these areas. And the act basically states that the major purpose of the "Kuchel" lease lands would be for waterfowl production, but with full consideration for commercial agriculture as long as it is consistent with the major purpose of the refuge. And so thatís kind of how the Kuchel Act fits into this. Does that answer your question?

STATEMENT I know a lot more now then when I started.

Green: Thereís more details in the Kuchel Act. It also directs us to give 10% of the lease land revenues to Tulelake Irrigation District (TID). Okay, TID actually operates and maintains these areas on Tule Lake for Reclamation and in return they receive assessments on the lands, for each lease lot, in the amount of $37 dollars an acre for delivering water on it. The other part in the act directs us to give 25% of the net lease revenues to the three counties involved in the areas and thatís on a pro-rated basis. That amounts up to $225,000 dollars a year that are dispersed between the three counties.

QUESTION: Hey Mike, in the flood/fallow concept of these seasonal wetlands, is it flooded once? I mean do you have to worry about issues of cholera, and botulism when you have, is it just loaded once and then its allowed to go down with the season?

Green: Actually no. It has two purposes 1) for waterfowl habitat production, 2) for Integrated Pest Management (IPM). In order for us to achieve IPM, especially in terms of white rot control, we really need to keep water on it during the hottest periods of the summer. So we donít drain the water down; we actually need to keep water above the soil with at least a few of inches on top. We havenít had any botulism or cholera problems out there that I am aware of.

Fran Maiss: Botulism thatís correct. Cholera happens within the basin any time you have concentrations of waterfowl, especially associated with lots of snow geese, so we have had some cholera there, but cholera is going to be where the snow geese are, so it is not really an issue. Weíve been fortunate in that we have not had any botulism issues, and I can talk a little bit about this program too during my presentation. Itís a real viable management tool.

Lane: Is there a difficulty in implementing a sump rotation plan, which I think is the name, which I know is the name of the strategy in the Kuchel Act? Is there tension between the desire for that management and the wording in the Kuchel Act?

ANSWER: Yes, if you're talking about sump rotation, the whole concept of sump rotation would be taking the water out of here, placing it here, and farming this area, and rotating these sumps. And the current plan is to break these up into halves or thirds and flood certain sections. There is a problem: the Kuchel Act requires us to maintain the 13,000 acres of Sumps 1A & 1B underwater or in wetlands. So we have to be careful if we dewater these areas to make sure that we're flooding up an equal replacement.

COMMENT: Just one more layer of complex issues. Youíve got all the ESA issues too, and the sucker habitats. Bald eagles too, which could be a positive. Sump rotation concept could be a positive factor.

Green: Luckily when most of those farming activities are going on during the summer, most of our eagles are away from the refuge, being a migratory bird. So we donít seem to run into many conflicts with endangered species. We are concerned about pesticide use and our endangered suckers that are in Sump 1A, and to make sure that we protect them, weíve implemented buffer zones around the lake, the drains, and the canals to make sure we donít have any drift into the waters. That program is closely monitored by the Department of Agriculture in Modoc and Siskiyou Counties

Okay, anything else?

Dow: This is just probably a very ignorant question but, when you're talking about two states and you actually have residents of California on this lease and you have Oregon residents as well, are there political implications because of the two states?

Green: Not in terms of management. We basically have adopted Californiaís pesticide's regulations as the baseline for our acceptance of pesticides on here, which has a stricter program than Oregon, and so in both areas up here in Oregon and in California we use Californiaís standards. People do live on both sides of border and even on the private lands a lot of growers farm both sides of the line, so really to the best of my knowledge, doesnít impact their operations, or theyíve adapted to it.

Keppen: Politically though, it allows Congressmen like Earl Blumenauer that are in Portland in our Oregon district, and Congressman Mike Thompson from the lower coastal area to introduce legislation intending to modify actions. The last two years theyíve introduced language to amend appropriations, congressional language, to modify what farmers can do. And basically, the last years of maneuvering have been intended to eliminate row crops as part of the program. But row crop farming is already pretty well limited as defined under the Kuchel Act. But you do that and the folks that farm that area clearly see that as a punishment because it takes away one of their prime sources of cash flow. There was a lot of this kind of myth making as we had to deal with that issue over the past two years. It has been defeated both times but with pretty contentious debate on the floor of the House of Representatives.

Green: You know that was real issue back in the 60s when Congress debated the Kuchel Act Bill, because at that time they didnít know if row crops had much value and assumed they had very little value for waterfowl production. So they capped it; they said no more then 25% of the lease lands can be in row crops. Currently we only have about 13% of it in row crops. There is space to expand, but itís really the markets that control how much are grown down there. We did a 4 year study on the wildlife use on lease land crops conducted by Refuge staff in-house and they actually determined that there was more dark geese use on the potato fields in the fall then there was in the grain fields, which was kind of an eye-opener to us, because we donít get a lot of reports from row crop farmers, regarding wildlife use out there. Weíre learning more every year about that.

QUESTION: Is your concern with pesticide usage because you know it gets into the water, or is it your concern with keeping them from getting into the water?

Green: Keeping it from getting into the water and certainly into the food chain.

Keppen: Is there a smoking gun regarding pesticide use and dead waterfowl out there?

Green: We have been looking for years and years and we cannot seem to find a smoking gun.

Davis: It goes back to that study I mentioned earlier, the two-phase study. Pesticides was a major focus of those two studies, and again there was no smoking gun in that, and those were really, really intensive. The second phase was very intensive with issues of ducklings, and all kinds of stuff, fish, and basically it came back clean.

Keppen: And thatís another one of the myths that we deal with. Really I think itís coming from the Wilderness Society, and some other national type environmental groups. The fact that thereís commercial farming going on on our Wildlife Refuge drives them crazy, and so almost every year we're facing some sort of legislation or litigation aimed at removing farming or minimizing farming on the lease lands despite the fact that there is no smoking gun.

Nelson: If you people were going to rewrite the Kuchel Act, first of all would you do it, and second of all, how would you do it, if you were going to rewrite it?

Keppen: Reaffirm it. Itís a good law.

Dr. Harry Carlson: If I might, it really is one of the few examples of federal legislation in a natural resource issue that worked, and I think that it is important to say that that is possible. At the time, 1964, you had two hugely powerful political camps; one wanted to homestead all of the acreage for maximum economic return to the community, the other wanted to preserve it as a waterfowl refuge, and it was destined to be homesteaded. So this was compromised legislation written to, if you will, appease both groups by preserving the waterfowl benefits of that land, but still allowing the full commercialization of the ag ground. And so what you donít have out in the lease lands is you donít have power lines, you donít have abundant roads, you donít have buildings, you donít have impediment to the waterfowl utilization of those fields. But you're getting some of the best farm ground in the basin, and some of the highest yields, and the highest economic return and multiplier affects occur down on that lease land, hugely popular with the agricultural community and the local counties. At the same time theyíve preserved the waterfowl benefits, and so in we probably could not return to historical bird use in the refuge without those crops out there. Itís a huge feed source, a high energy feed source for the birds. So to me the legislation is a rare example of legislation that did exactly what what it was intended to do. And while it does, it currently gets a lot of criticism simply because there are people that believe a red combine parked out in the middle of National Wildlife Refuge is not what they want to see. So there is that incongruous, if you will, aesthetic concern that will always come up. But the act is probably one if the best federal acts on the role, in terms of actually accomplishing what they set out to do, and it is working as well today as it did when it first passed.

Lesley:

Thereís an awful lot of innovation that is being done on the lease lands in agriculture too. I think itís one of the test beds for different methodologies and treatments in crops, and ag practices for the basin. We encourage it and we support it, so itís been a real benefit I think to agriculture in the basin in the things that have come out of the lease lands for use in the general area.QUESTION: Has it been expanded to the private lands, the technology transfer concept.

Carlson: Yes, I think the seasonal wetlands or CRP type opportunities on private ground to manage private ground like they are in the refuge should, people are looking at it and it may have a huge impact on habitat.

Davis: As Cecil was saying, the lease lands are kind of a test bed for many things, and as we experiment and establish practices for sustained agriculture on the lease lands, then that becomes really a good test pit again for the surrounding private properties. And we see that kind of technology, those kinds of practices, transferring over, not just within the basin and there around Tulelake but in other areas.

Green: This year, for example, was the first year that we required flushing bars on hay swathers for the alfalfa fields, and so that technique really hadnít been implemented here in the basin that I know of, so by encouraging the growers and actually writing it into their contracts this year they did it for the first time and it turned out that it wasnít so painful as they thought it would be to implement. The flushing bars certainly helps the growers to flush the adult ducks off the nest so that we're not compromising their existence.

Karas: There are other even further reaching implications. One of the emphasis here is to be able to hold birds in this area to reduce carp depredation in Central Valley, so itís complicated, a lot of complicated issues.

Richmond: Mike, is some of this work on the rotation between seasonal wetlands and agricultural uses, is that written up some place that you can go read about it? I mean that strikes me as being a really very important contribution, one that Iíd like to learn more about.

Green: Yes and Iíd be glad to send some your way if youíd like. (If someone would to request an Integrated Land Management (ILM) Plan, they can do so by contacting Dave Mauser, Refuge Biologist @ 530-667-2231.)

Davis: About what was it Terry? Two years ago there was a committee that was put together that did a concept plan for "the sump rotation" we put another name on it that I never can remember. Integrated Land Management Plan, sump rotation is my graphic, but anyway we can provide you a copy of that.

Karas: Thanks Mike, Okay next up would be Fran whoís going to talk a little bit about the refuges.

Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge and Tulelake Refuge

| Fran Maiss: Iíd like talk a bit about the two main refuges in our complex and that is Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge and Tulelake Refuge. Getting back to the historical context, we heard some about the development of the Project. Basically the Lower Klamath Lake was about a 80,000 acre lake, natural lake, that was drained in the early 1900s in an attempt to convert it to agricultural uses, and how it shook out was the Oregon part of the lake proved itself to be viable for agriculture and the California side much less so. And so what happened was all water had been cut off, as Mike mentioned, by the construction of the railroad and the placement of the gates. And so from 1917 until 1942, the California section of this area was basically a dry lake bed, and actually a dust bowl situation. |  |

On the other side, Tulelake Refuge was being converted to agricultural use and they had a fluctuating reservoir dependent on the winter time precipitation that lent problems to converting certain areas to agricultural use. So they came up a concept in the 1940s of putting a dike around the fluctuating body of water and drilling a tunnel through Sheepy Ridge, and any excess waters that came into this pool could be pumped back into this dry lake bed. And that is how we ultimately came up with water again on Lower Klamath Refuge. So, 1942 the tunnel was put in and water was pumped in. It was basically one big or one fairly large body of water. From 1942 until this date we have evolved a management style that has used water that was in excess of Project needs, but these two refuges are totally connected to Project infrastructure and all water is artificially delivered.

|

<

Map 1 Larger LK Map 1 -- go HERE. In the early 40s, this body of water was basically unmanageable and we did have botulism issues and so in the 40s it was diked into 3 cells in an effort to be able to control individual bodies of water mainly for disease control. That concept expanded over the 1950s and 60s to where this refuge was subdivided into about 15 cells. And then in the 1970s that subdivision was further refined to control of water on smaller units so we could mainly control the disease of botulism. In the 1970s and 80s waterfowl management evolved into production of moist soil plants, growing native wetland plants for seed production to feed waterfowl on their migration. So in the 70s and 80s this was further subdivided from about 15 units up to the current 34 units, which is depicted on this |

There are two primary methods of water delivery to Lower Klamath. One is the ADY Canal which is a direct diversion out of the Klamath River that gives us roughly at full capacity about 117 CFS. That historically has provided about one-third of the water needs for this refuge. The other source of water is this D Plant that pumps excess waters from Tule lake across into Lower Klamath, and that historically has given us about two thirds of our water supply. We basically have evolved the management style over 60 years through construction of levies and managing units independently for various different biological outputs. Lower Klamath is one of the most productive wildlife refuges in the entire system, and certainly in the Pacific Flyway, irrespective of the season. This is a map showing the habitat types that we had planned on for the year 2003. In purple is what we we're planning to have in permanent marshes.

The biological value to permanent marshes is that they are production units in the summertime for water birds and waterfowl. We have a lot of colonial nesting birds, a fair variety; we have pelican and cormorant, white-faced ibis, heron, egret, that are tied to these permanent marshes. These are also quite prolific waterfowl producers, mainly ducks. In the green we have what are seasonal wetlands. These are marshes that we flood up during the fall and winter, and we dewater them by the middle of June and we let them sit in a dewatered state, growing moist soil plants, until the first frost, which would be mid September or so, and these wetlands are very prolific producers of wetland plants, seasonal plants, smart weeds, and goose foots. We then flood these units in the fall for the waterfowl migration. The fall migration through the Klamath Basin varies from about 15 to 20 million birds annually. Thereís some fluctuation dependent on production. But about 80% of the waterfowl in the flyway come through the basin. A full 50% of those birds that come through the basin traditionally have stopped at the Lower Klamath Refuge.

The peak of migration occurs about the first of November. Then getting into the wintertime we have a certain level of waterfowl, mainly ducks, that over winter. We pick up large populations of tundra swan on their northward migration in late January and February and during that time we have a peak of one of the largest bald eagle populations in the lower 48 in the Klamath Basin of which about half use Lower Klamath and the waterfowl resources that are over wintering there. And in conjunction with that we have a major eagle roost on the Bear Valley National Wildlife Refuge, which is a timbered ridge basically about 4000 acres of mature trees. An eagle would fly about 5 or 6 miles between these two refuges, and Bear Valley is basically a nighttime roost and they come to the Lower Klamath refuge to utilize waterfowl. Over the last three years weíve had very sporadic water deliveries compared to our historical management, so itís a challenge to manage this refuge in its historical context, and to maintain the large array and diversity of wildlife species.

This summer we had attempted to maintain this level of whatís in purple (MAP 1 above) here as a permanent marsh. That acreage was about 9000 acres and we have learned that, with our only source of water in the summer, reliable source being the ADY Canal, we can only run between 8 and 10 thousand acres of permanent marsh because we need a certain amount of water to offset evaporation, which was mentioned itís roughly about 3 feet of evaporation. And these marshes are only 2 to 3 feet deep at maximum anyway, so they are shallow marshes. We were notified because of the water year type in June that we would not be able to utilize the ADY Canal this summer, so we had a 2-month period from the middle of June to the middle of August that we received no water deliveries and so what we had to do was basically cannibalize some of our permanent marshes and dewater them in favor of other marshes, the more productive ones, to keep some viability to our permanent marshes.

|

< Map

2 Larger LK Map 2 go HERE And what we did was, we basically drained out unit three (MAP 2) here into unit two to keep it viable and we drained this string of marshes to keep these two up. Then in the middle of August we were told we could utilize 25 CFS out of the ADY, which is a rather minimal flow, because normally over the summer we historically took the full 117 over the summer to keep this level up. Weíve been receiving about 25 CFS for a month that essentially has allowed unit two to refill, and on the D Plant side in early August, Tulelake Irrigation District told us that the water levels were approaching the upper limits of the levyís over there so they were going to turn on a couple of pumps and they pumped two pumps which is 140 CFS for about 3 weeks. That allowed us to refill some of what we have drained. We refilled unit 3 and we topped off or tried to unit 8 and 12 C. |

But the problem with that type of management is by dewatering a permanent marsh, what youíve done is that youíve lost your sago pond weed beds, which are the underwater structure thatís going to feed the diving ducks that come in the fall. By dewatering it for a span of a few weeks youíve actually eliminated that food source from the marsh, so when you reflood it, on the surface it looks the same, but under the surface it's not. It does not have the productivity for the fall flight of diving ducks.

Normally we would start flooding, and we have started flooding, the 1st of September we start flooding our seasonal marshes. We have about 10,000 acres total. We like to have about Iíd say 6000 acres flooded by the peak of migration, which is the first week in November, and currently the Bureau told us this week we could bump up the ADY to 50 CFS and we currently have one pump coming through the hill. So we have started flooding some of our seasonal marshes but it's not really possible to plan anymore with the sporadic nature of water deliveries, especially in this being a dry or below average year, which ever.

The type of management that has evolved on Lower Klamath Refuge is very hard to maintain under the current sporadic water deliveries. We also have some grain fields within the mix and we utilize them for two reasons. Mainly, many of our units our farmable, so we rotate farming in order to keep seral stages of wetlands, evolving from early seral all the way through mature marshes. And grain fields are crop shared grain fields so a quarter of them are left standing and they do provide habitat to grain feeding waterfowl and actually sand hill cranes. We get about almost 80% of sand hill cranes in the Pacific Flyway stop in the summer and on the fall flight also. So there are major challenges with this refuge, managing the way we have evolved our management strategy, and now with the current changing of water priorities and water deliveries, this refuge has some major challenges in front of it.

Moving on to Tulelake Refuge, thatís kind of the bad news (Lower Klamath NWR), this might be the good news or silver lining or whatever. Historically Tulelake Refuge has been two large bodies of water Sump 1A and Sump 1B, that stayed fairly static in water levels. Static water levels in a wetland over time leads to decreased productivity. So what we done recently in the past 6, 7, 8 years with the help of Tulelake Irrigation District, the Bureau of Reclamation, and Ducks Unlimited, we were able to transform Sump 1B, which was a permanent body of water. We put in the infrastructure to make it seasonal, and itís been a seasonal marsh now for three years. So we are getting a very good response from seasonal management there and seasonal plants.

As Mike alluded to, we have some rotational wetlands now out on the croplands. These are the two main blocks of cropland (see Map). We're doing a lot of research on integrating rotating wetlands within the leasing program and within croplands. This particular one is a multi-year wetland that was created out of former crop lands and this is the flood fallow program where it is a one year flooding in order to purge the soil of soil born pathogens. We plan to do the one year flooding annually at that size or slightly bigger 600 to 1000 acres, moving it around the refuge so that over a 10 or 12 year period the entire area has been treated once.

We have developed a concept document called Integrated Land Management on Tulelake Refuge. There are four different scenarios or strategies. Thereís actually an infinite number of strategies. You could come up with any configuration, enumerable configurations, but weíve outlined four that a group, that group that we put together, analyzed all the issues, and came up with four possibilities so were pursuing that too. Basically, get an integrated method of wetlands and croplands in rotation and actually looking at taking some of the long term historic wetlands out and breaking it out into agricultural production, and we feel that that has a lot of possibility. As Harry mentioned, this is the most productive farmland in the basin, and consequently it produces the most productive wetlands in the basin. Doesnít matter what crop your bring off this land, itís going to be highly productive, whether itís a wetland or whether itís agricultural crops. So we would like to get into a rotational scheme that would we feel enhance both agriculture and wildlife values.

The seasonal marshes that weíve made here, weíve made some other ones. These were some of our experimental marshes that we did initially to see if the concept would work on a small scale before we went big on a larger scale, and we feel that the ability to get water to these seasonal marshes on the Tulelake side probably has a higher probability due to the return flows that come from the Tulelake Irrigation District plus the irrigation district's interest in working with us and they also have deep water wells that have some capability to flood these wetlands. And so we feel any seasonal marsh that we develop on this Tulelake side has a higher probability of being flooded then the ones on the Lower Klamath. We have evolving strategies on both refuges. We have some fairly significant issues on Lower Klamath, but we are working to try to enhance the productivity of the Tulelake refuge at the same time, so itís kind of a mixed message Iíd say.

QUESTION: The productivity of this soil is due to the peat?

Maiss: It is due the lakebed nature of the soil, itís very deep. Itís organic.

QUESTION: What about that southwest sump, did you talk about that unit?

Maiss: This is an agricultural unit, I believe it's 5000 acres, but itís an agricultural unit very much like this except that we have not yet ventured into the realm of wetland rotation in this sump. Sump rotation has been a concept that has been around some 10 or 12 years and we have refined it. With what we're doing here, this probably will stay in agricultural sump with water moving around in it in its current fashion as integrated pest management technique. What we might do down here is have some sort of a permanent deep water restoration and the trade-off for permanent piece of agricultural ground of equal size or similar size, and so we havenít quite ventured into here on this scale pending sump rotation.

We have an engineering study on both these refuges, very in-depth engineering study, that we should have the end result by the end of this year, and one of the aspects of the study is on the Lower Klamath side looking at our current infrastructure and how we can modify our current infrastructure to better utilize water. And a second piece of that would be if we could create new infrastructure here is what we could do to better utilize the water that we get. On the Tule Lake side they are analyzing from an engineering standpoint the costs that would be involved in doing one of the sump rotation scenarios with a possibility to be able to interpolate that data to any type of scenario that you might come up with. So when we get that in hand we'll be further down the road because cost as always is a big factor, we really donít have a clue. So when we get an engineering detail on one of the scenarios weíll have a ballpark estimate of cost. Then I think we can go public with scoping on the concept, get feedback, and start moving down the realm of actually possibly implementing it, probably in stages.

Nelson: I understand that Pacific Power or as I like to call them Scottish Power is going to renegotiate the electric rates as part of a FERC the same time the FERC proceedings go forward. What effect will that have and do you use a lot of electricity that you pay for?

Maiss: Right now we are almost entirely gravity flow other then the infrastructure that the Tulelake Irrigation District uses which is D Plant. I didnít mention but we did develop some ground water on the Lower Klamath side. We currently have one deep water well developed. Weíll have two more on line this summer. The total capability of our development of ground water on the Lower Klamath side is going to compute to roughly 40 CFS so I believe how we plan on using that is to run some permanent marshes and just try to offset evaporation by pumping. That amount of flow wonít maintain that large amount of wetland acreage, but maybe a quarter of it, something like that, so every little bit helps. So there are electric costs tied to that. Currently weíre getting the Project rate, which is very good. How that shakes out in the future I really canít answer. Maybe the Bureau knows the answer to that one.

Bob Davis: Itís going to be larger.

Lane: Since producing wetlands acquires wet, and thatís water, on the Tule Lake side, you described a really good sounding program but it relies on the availability of water. So you could still be in a situation where it would be great to do that rotation, but if we get into years where water is limited, that year is going to just to fall out. Is that the way it worked out?

Maiss: I think I have a higher expectation probably of water, possibility of water being available on the Tule Lake side because of the close connection of the infrastructure of that irrigation district and the return flows. Actually, if this is part of an agricultural program, it may be a legal question, but there is a legal priority for water as you know and agricultural use of water has a higher legal standing then refuge wetlands, and so it tied into that. I have higher hopes for water being available on the Tule Lake side then I do on the Lower Klamath side.

Davis: The other factor that we need to keep in mind: those waters are also a part of the biological opinion on suckers. We do have endangered suckers that are in that area, and whatever happens in this sump rotation concept, we would need to consult on that. And thereís a Kuchal Act requirement that it might be not smaller then 13,000 acres, and so water will still be a factor there.

Maiss: But like Bob mentioned, this particular sump does have a population of endangered suckers. There is currently a minimum water level attached to that sump in the biological opinion so this unit always has water irregardless of the water year. Any new configuration that we came up with, with paramount importance would be adequate habitat for this population of suckers. That would be the first thing weíd have to provide.

Davis: Actually, in 2001 when we had to shut off deliveries for Upper Klamath Lake, it jeopardized the water levels in Tule Lake so we actually brought water from Clear Lake and Gerber, brought that water around in order to sustain Tule Lake, because of the endangered species that are in the lake area.

______________________________________________________

#6 o Klamath Basin Ecosystem Restoration