|

http://www.northcoastjournal.com/071207/news0712.html

The Klamath knot

Will frustrated enviros, Dick Cheney jam the

settlement?

By Japhet Weeks, 7/12/07

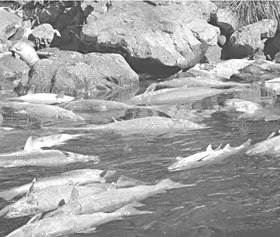

Klamath

River. Photo courtesy of Jim Simondet, NOAA Fisheries. Klamath

River. Photo courtesy of Jim Simondet, NOAA Fisheries.

This summer is already proving to

be another difficult one in the Klamath Basin, both on and off

the river. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently

issued a warning about dangerously high levels of toxic algae

blooming on the Klamath River in Iron Gate and Copco

reservoirs. And the Klamath Fish Health Assessment Team --

made up of biologists with state and federal agencies and

Native American tribes, among others -- have increased the

fish die-off readiness level from green to yellow, meaning

that the fall Chinook and coho runs could be in danger this

year.

Meanwhile on land, 28 disparate

stakeholders including the states of California and Oregon,

U.S. water and wildlife agencies, fishermen, Native American

tribes, farmers and environmental groups have been negotiating

a settlement behind closed doors for over two years about how

to share water in the Klamath Basin, and what to do about

PacifiCorp’s hydropower dams there. As their negotiations

proceed, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is working

in parallel to complete its final environmental impact

statement, which will determine whether or not to relicense

PacifCorp’s Klamath dams. The group of stakeholders is trying

to balance the protection of imperiled fish species --

including salmon, two types of sucker fish and the bull trout

-- along with national wildlife refuges and the interests of

farmers who depend on river water for their livelihood. The

task doesn’t just sound Sisyphean. It is.

“If it were easy, it wouldn’t be

hard,” said Greg Addington, executive director of the Klamath

Water Users Association, which represents irrigation districts

in the upper basin.

Unfortunately for the stakeholders,

things don’t look like they’re going to get easier any time

soon. Two out of the 28 groups are no longer at the table --

Oregon-based non-profits Oregon Wild and WaterWatch of Oregon,

which were pushing for the complete phasing out of commercial

farming on the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath national wildlife

refuges. These groups came to loggerheads with other

stakeholders, and, according to representatives, ended up

being excluded from negotiations, which have moved forward

without them.

“It’s because they weren’t looking

for a solution ... Their agenda is to have agriculture out of

the upper basin,” said Addington.

Steve Pedery, conservation director

of Oregon Wild, sees it differently. In a July 5 op-ed in the

Eugene Register-Guard, he wrote that the Bush

administration and its agribusiness allies “hijacked

closed-door talks over the removal of four Klamath River dams,

demanding that conservation groups, tribes and fishermen

support permanent commercial agricultural development on the

Klamath’s spectacular national wildlife.”

Reached by telephone while on a

canoe trip on the Williamson River, which flows into Upper

Klamath Lake, Pedery explained that last summer he thought

things were “fairly positive” as a result of “traction” gained

in the talks. But then the federal government put a

“settlement framework” on the table, which stipulated

“permanent refuges for agribusiness” in exchange for dam

removal. That’s when Oregon Wild was told “to sign or else.”

When they and WaterWatch refused to do so, they say, the

negotiating committee was simply dissolved and subsequently

reorganized without them.

“Compromise isn’t ‘Four groups get

in a room, two make a deal and force it on the others,’”

Pedery said about his experience at the negotiations after the

framework was introduced. Nonetheless, he said Oregon Wild

continues to be involved in the process through sister groups

and allies in the tribes.

Bob Hunter, a staff attorney at

WaterWatch, is worried that without his group and Oregon Wild

at the talks, a resolution will be far from ideal. “Our

concern is that without us at the table, we could end up with

a deal where people might be touting that they solved problems

in the basin while keeping the same level of demand [for

water] that has been driving the basin into crisis from year

to year,” he said. But he was optimistic that WaterWatch will

eventually be allowed back in.

Craig Tucker, spokesman for the

Karuk tribe, said the framework, which Pedery claims was

foisted onto the stakeholders from above by the shadowy powers

that be, was in fact the result of arduous negotiating among

the disparate groups. “We achieved working out a framework

that specified dam removal,” Tucker said. “Everybody felt it

was good for the river except for Oregon Wild ... We didn’t

want to stop making progress because of what we perceived as

Oregon Wild’s ideological concerns.”

Furthermore, Tucker downplays the

group’s importance to continuing negotiations, calling them a

“relatively small group” out of touch with basin residents.

Nor does Tucker buy Oregon Wild’s conspiracy theory. The

negotiation committee has “not been hijacked by the Bush

administration. It has been hijacked by the people who live

here,” he said.

However, in light of recent

allegations by the Washington Post that Vice President

Dick Cheney reached down from the Olympian heights of the

White House to force his hand in the Klamath Basin in 2001,

Pedery’s concerns are not without precedent. The four-part

report alleges that in an effort to get former Republican

congressman Robert F. Smith of Oregon reelected (at the time,

Smith was representing farmers in the Klamath basin fearful

their crops would go unwatered for the sake of saving salmon),

Cheney called into question studies conducted by the federal

government’s own scientists which “concluded unequivocally”

that diverting water for irrigation would harm two federally

protected species of fish, violating the Endangered Species

Act of 1973. After the National Academy of Sciences had

“scrutinized” the work of federal biologists -- at the vice

president’s behest -- they found that diverting water for

irrigation into the Klamath Basin wouldn’t be that disastrous

after all. (In 2002, the science academy’s decision to divert

water to farmers resulted in the largest fish kill in U.S.

history.)

The lead biologist for the National

Marine Fisheries Service team, Michael Kelly, critiqued the

science academy’s report in a draft opinion, but his comments

were edited out by his superiors. Later, in a whistleblower

claim, Kelly, who has since quit the federal agency, said that

it was clear to him that “someone at a higher level” had

ordered his agency to endorse the proposal regardless of its

consequences to the fish.

WaterWatch’s Hunter said that

allegations of Cheney’s involvement in the Klamath basin raise

important questions: “Is that influence [Cheney’s] still

there?” he asked. “Is it still being exerted on the talks?”

Tucker, on the other hand, said

that the Washington Post series was a distraction, at

least to the people on the ground. “The news isn’t what some

politician did four or five years ago, it’s what we’re doing

today,” he said. And he added that there’s good news that

needs reporting: “By year’s end, we’re gonna have a negotiated

agreement with PacifiCorp or with everyone except PacifiCorp,

and FERC will issue a mandate,” he said.

In a process like the Klamath River

negotiation settlement talks, difficulties are to be expected,

said Greg King, director of the Northcoast Environmental

Center in Arcata. “There are a lot of salvos and inaccuracies

being lobbed which one might expect given the disparate

collection of groups and individuals in the room,” King said.

But what’s “amazing,” according to King, is that “the

disparate groups and individuals are still in the room three

years later.” That is, everyone except for Oregon Wild and

WaterWatch. But for those stakeholders left at the table, like

Craig Tucker with the Karuk tribe, it’s clear there’s no way

to reach an eventual settlement without making tough

compromises.

“At the end of the day,” Tucker

said, “we want to see a salmon and potato festival in the

Klamath Basin Valley.” |