The people v. FERC

Eureka hearing-goers

tell agency to drop the dams

story and photos by HEIDI WALTERS,

North Coast Journal 11/23/06

http://www.northcoastjournal.com/112306/news1123.html

It seemed like everybody was

there. Some had driven the riverine, twisty

highways out of the mountains of the

mid-Klamath region -- from Orleans, Somes Bar,

Salmon River, Blue Creek. Others came from the

mouth of the Klamath. Some moseyed over from

their Eureka homes or from Arcata and

McKinleyville, or traveled up from southern

Humboldt or Sacramento.

There were Yurok, Karuk and

Hupa people. There were non-Indians. Ocean

fishers. River guides. Congresspeople, or

their reps. There were college students,

scientists, kids, conservationists, city

people, river people and even a sympathetic

farmer or two.

It was Thursday night, and

inside the Red Lion in Eureka the Federal

Energy Regulatory Commission was holding a

hearing on its draft environmental impact

report for the proposed relicensing of

PacifiCorp's Klamath River dams, now owned by

billionaire Warren Buffett. The Klamath

Hydroelectric Project's 50-year license

expired in March, and FERC is considering

relicensing the project for another 30 to 50

years. This hearing was one in a series being

held across the region before the public

comment period ends Dec. 1.

But, just like the last time

FERC came to town for a Klamath River meeting,

the agency had underestimated the numbers that

would show up. Even before the official start

time of 7 p.m. arrived, the long, narrow room

was already packed to the gills -- 250 people,

the maximum allowed. Further entry was barred

in order not to incur the wrath of the fire

marshal or induce death by suffocation among

the attendees.

So for the next nearly five

hours, about 150 thwarted people wriggled up

and down the long, tight, packed hallway

outside the hearing doors, waiting for a

chance to be let in as others left. Some of

them gave up and went home. Many wandered in

and out of a room across the hall from the

hearing that the Northcoast Environmental

Center had reserved for the anticipated

stranded attendees. There were speeches,

protest signs -- "Un-dam the Klamath!" -- and

informational posters and a new video by the

Klamath Salmon Media Collaborative called

"Solving the Klamath Crisis: Keeping Farms and

Fish Alive."

Inside the NEC room, biologist

Pat Higgins was explaining to a passerby the

Klamath's water quality and temperature

problems and the dams and dikes that have

caused them, and how FERC's recommendations in

the draft EIS fall short. He and other

critics, including the National Marine

Fisheries Service, say FERC's draft EIS

analyzes the removal of just two dams, when it

should consider removal of all four of the

lower dams -- Copco I and II, J.C. Boyle, Iron

Gate -- that have blocked fish from 350 miles

of river for decades. FERC staff, instead,

recommend trapping and trucking some Chinook

salmon around the dams to repopulate a portion

of upstream river. Critics say such a plan is

weak, and besides would do nothing for the

other species who once had passage to the

upper reaches, such as the coho salmon,

steelhead, lamprey and green sturgeon.

"Trap and haul -- they tried

it in the `60s, when they built Iron Gate Dam,

and it didn't work," Higgins said. "I think

they need to take the [four main hydro] dams

out. They need to leave Link River Dam, which

regulates water levels in Klamath Lake, for

the fish. And if they leave Keno Dam, they

need to restore the wetlands adjacent to the

Klamath River in that reach."

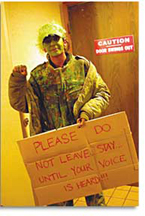

Back out in the hallway, the

crowd grew. Even Toxic Algae Monster was

there, haunting a corner by the kitchen doors

in her green fuzzy hat, green-painted face and

green clothes and holding a big cardboard sign

that said "Please don't leave. Stay until your

voice is heard!!!" Rani Rhoar, who's lived in

Orleans by the Klamath River for 12 years,

said she was at FERC's hearing in Yreka the

day before and at a water quality board

meeting in Sacramento before that. But this

was the first time she'd dressed up as the

toxic algae that has been increasingly

plaguing the river and its reservoirs.

"When I first moved to the

Klamath River, I used to swim in it," she

said. "Today, I don't swim in it, I don't raft

in it, I don't touch it. They need to remove

the Klamath dams and restore the river. And

make humane decisions."

Standing near the algae

monster were fellow Orleans residents Quentin

Peterson, with blue and purple dyed hair and

earrings, and Richard Buhler, whose bright red

dyed hair, red-satin-lined black trench coat

and kind young face made him look like a

friendly devil. (Unlike the algae monster,

this is their usual look.) They grew up in

Orleans. Peterson's a firefighter, crab

fisherman and part-time river guide. He said

he tries to make it to every river-related

meeting he can. "My dad was a river guide my

whole life, drift-boat guiding and rafting

trips. I was raised in a boat. I caught my

first fish when I was 3 years old." He and

Buhler reminisced about the rope swing they

used to play on that hung from a bridge over

the river. "Now I won't go in the Klamath,"

Peterson said. "I won't let my animals in the

water. I took people out rafting a couple

times this summer, but we had to go to the

Salmon River instead. We canceled a couple of

trips. I was there for the fish kills in 2002

-- there were so many dead fish, we couldn't

get the boat in the water. Also, half the

reason I go to the river is its beauty. Now

it's gross. There's algae hanging off the

rocks, every pool is stagnant."

Buhler, who crews on salmon

and crab boats, said for this year's salmon

season -- closed in Oregon and California, for

the most part, because of low salmon counts in

the Klamath -- he had to go to Alaska to work.

"I would prefer to stay here," he said. "But

if you fish for a livelihood, you can't skip a

season."

Down the hall, Nat Pennington

wanted to talk about the Salmon River, where

he lives. It's un-dammed, and the cleanest

major tributary to the Klamath River. But it

has had "the three lowest runs of spring and

fall Chinook in record history," said

Pennington. "So we feel like the water quality

issues created in the Klamath are a major

impact on our salmon runs."

Near him stood Jason Reed,

who'd just been interviewed by a TV station.

Like many of the young men there that night,

he wore a knit cap with traditional tribal

designs. Reed, a College of the Redwoods

student, is Karuk and Hupa. "Salmon is like a

family to us," he said. "What are we going to

do when the salmon is gone? I was raised on

the river. I remember there being lots of

fish. I remember packing -- in gunny sack's --

like, five fish at a time. And this was just

one round. Pack 'em, clean 'em, and go back to

the river again for more. Today, we're lucky

if we get five."

Back at the other end, Hoopa

Valley Tribal chairman Clifford Lyle Marshall

and the tribe's senior attorney, Grett Hurley,

stood talking. "I'm surprised that there

aren't more people here," Marshall

said. "[But] this is a healthy showing. It's a

reflection of the widespread concern. It's not

just Indians and it's not just fishermen. It's

people from Eureka. And other places."

| Finally, some space opened up inside

the hearing r oom. There, rows and rows of

people -- including several children,

holding large salmon puppets on sticks,

from the American Indian Academy Charter

School in McKinleyville -- faced a table

at which sat three FERC men. One after

another, the people stood and delivered

lengthy speeches, some fact-filled, others

emotional. |

|

The FERC men, their job here

simply to listen, sat silently -- white, gray,

impassive, eyelids fluttering shut. They

hadn't taken a break, and no doubt were weary.

Even so, the scene seemed like the

personification of a choked river full of

desperate salmon leaping at an immovable

concrete wall.

State Senator Wesley Chesbro

was just getting up to speak. "You can hear

the frustration in the voices" of these

people, he said. The draft EIS, he said, was

flawed, and FERC should tear down not two

dams, but four -- and the state would be there

with the cash to help restore the river.

| Then a familiar figure

took the floor. As he spoke, the crowd

tensed and glared at him. "My name is

Dennis Mayo, I'm a native Humboldt County

boy," he said. He warned that he might

offend some people. "I'm here tonight to

make comments from the farming and

ranching community, and also as a

recreational fisherman and a past

commercial fisherman and an avid duck and

goose hunter. I have farmed and ranched

throughout the Klamath Basin and I

currently have stock on feed in the upper

Klamath. My community is sick and tired of

the almost xenophobic way the

environmental groups have attacked us and

our livelihood. It has to stop. In the

past we have been played off against the

native and fishing communities in every

conceivable way." |

Right: Rani Rhoar, toxic algae monster. |

Mayo accused environmentalists

of hurting "working folks" and helping destroy

rural communities. He told FERC they were not

to be trusted. But then he said: "We want FERC

to know that we don't need these dams for our

irrigation, or flood control, and that we are

getting no benefit from the meager electrical

output. We want FERC to know that the Klamath

dams have not only lived out their usefulness

as electric generators, they might have also

lived out the life blood of the river: the

salmon. If that happens and the salmon die,

also dies the life blood to the soul of the

Klamath's native peoples. That cannot be

allowed to happen. We want to tell FERC that

we will see to it that our neighbors are not

stomped on, broken or bankrupted as we make

sure these dams are decommissioned."

He implored the by-now

confused "enviro community" to "get off the

superiority trip," and he asked the Northcoast

Environmental Center to pull from its website

"the discriminatory caricature of a fat

cowboy/potato farmer with his pockets stuffed

full of cash."

After that, a Yurok man

remembered three kids who'd gone swimming in

the river, even though they were told not to,

and came out covered in bumps. A commercial

fisherman said he's fished for 30 years in the

ocean, and though he's suffered from the

recent restrictions, his "heart goes out to

the Indians" more. Lyn Risling, Karuk-Yurok

and a Hoopa Valley Tribe member, likened the

loss of traditional foods such as salmon,

deer, acorns and berries to a continued

genocide of her people, ravaged now by

diabetes and other ills.

Back out in the hallway, Dale

Ann Frye Sherman -- half Yurok, half Tolowa --

and Yurok Tribe members David Gensaw, Sr. and

Willard Carlson, Jr. were getting ready to

leave. They hadn't had a chance to give their

comments yet, but midnight was approaching and

some people had to work the next day. They

seemed deflated.

"They're going to do it

anyway," said Gensaw about the FERC team.

"Their attitude -- they don't even want to be

here. They're falling asleep. And why are we

pleading? We should be demanding!"

"They don't even live here,"

said Sherman.

"If they don't tear those dams

down, and they get relicensed, the writing's

on the wall," said Gensaw. "The salmon will be

gone."

"And, in essence what that

means is, we as a people will be gone," added

Sherman.

"You can't convince me it

wasn't a conspiracy," said Gensaw. "If they

kill the system, if they kill the fish, then

they won't have a fight for the water. The

water's like oil. We've got a war on because

of oil. But you can live without oil."

They talked about the fish

wars in the 1970s when the federal government

showed up in the Indian river communities

wearing riot gear while the Indians fought for

their traditional fishing rights.

But there was a glimmer of

hope, they admitted. "This is the first time

I've come to the Red Lion [for a hearing] in

years that the people didn't say, `The Native

Americans overfished with their gill nets,'"

said Carlson, who lives on Blue Creek, a

tributary to the Klamath.

"They used to be our enemies,"

said Gensaw about all the non-Indians at the

hearing. "Now they're our allies." |